Johnstown was founded in 1800 by Joseph Schantz, also called Joseph Johns, a Pennsylvania German immigrant. The first ethnic church in Johnstown was founded by German immigrants by about 1810. By the 1830s, Johnstown had developed into a small town, and the dominant ethnic group was German. Driven by economic hardship, larger numbers of immigrants began to arrive by the 1870s, and found work in the growing steel industry and the coal mines that fueled it. The Welsh, many of whom had been miners for generations, found work in the coal mines. Most Irish immigrants had originally come to the area to build railroads, and when that job was largely complete were hired by the steel mills. More Germans began to arrive, and by 1880 contract agencies in New York were sending train cars to Johnstown filled with Germans and Scandinavians.

Johnstown was founded in 1800 by Joseph Schantz, also called Joseph Johns, a Pennsylvania German immigrant. The first ethnic church in Johnstown was founded by German immigrants by about 1810. By the 1830s, Johnstown had developed into a small town, and the dominant ethnic group was German. Driven by economic hardship, larger numbers of immigrants began to arrive by the 1870s, and found work in the growing steel industry and the coal mines that fueled it. The Welsh, many of whom had been miners for generations, found work in the coal mines. Most Irish immigrants had originally come to the area to build railroads, and when that job was largely complete were hired by the steel mills. More Germans began to arrive, and by 1880 contract agencies in New York were sending train cars to Johnstown filled with Germans and Scandinavians.

The Irish, Germans and Welsh founded the earliest ethnic social clubs and organizations. The first German foreign-language newspaper, the Beobachter, began publication in 1855. By 1889, there were several Lutheran and Catholic German churches, and a few Irish Catholic churches. Johnstown was considered a “German” town. These Western European groups assimilated into American culture and became the most powerful, well-established groups in the Johnstown community.

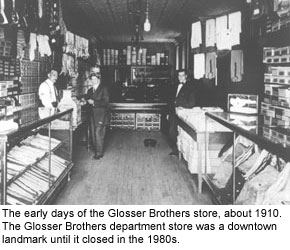

Jewish immigrants were fleeing persecution, so they came to this country intending to stay permanently. For that reason, they generally brought their entire families with them. Jewish immigrants were predominantly peddlers and merchants. The first few Jewish families, mostly Reform Jews from Germany, arrived by about 1850. During the 1880s the first Orthodox Jews began to arrive from Eastern Europe. Jews first met in private homes for Orthodox and Reform religious services, and synagogues and social organizations were founded around the turn of the century. Jews were excluded from most jobs – including jobs in the steel mills.

Jewish immigrants were fleeing persecution, so they came to this country intending to stay permanently. For that reason, they generally brought their entire families with them. Jewish immigrants were predominantly peddlers and merchants. The first few Jewish families, mostly Reform Jews from Germany, arrived by about 1850. During the 1880s the first Orthodox Jews began to arrive from Eastern Europe. Jews first met in private homes for Orthodox and Reform religious services, and synagogues and social organizations were founded around the turn of the century. Jews were excluded from most jobs – including jobs in the steel mills.

As the Cambria Iron Works became more successful and more mechanized in the 1870s and 1880s, its need for unskilled laborers grew exponentially. At the same time, the great wave of emigration from Southern and Eastern European countries (predominantly Italy, Poland, Russia, Bohemia, Hungary, and Slovakia) had begun, and many immigrants settled in Johnstown. The Heritage Discovery Center’s permanent exhibit, “America: Through Immigrant Eyes,” focuses on this wave of immigrants, who arrived from about the 1880s through about 1914. Unlike their earlier counterparts from Western Europe, many of these immigrants never intended to stay America permanently — instead, they wanted to save money to build a better life back home in Europe. Often men came alone, planning to return after earning enough, or hoping to establish themselves here before sending for their families. Nationally, about one-third of these later immigrants did return home, but most stayed in the United States permanently.

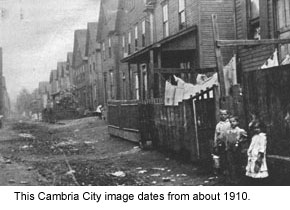

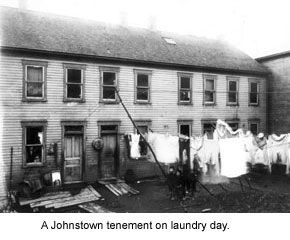

These new arrivals to Johnstown faced prejudice and difficult living conditions. From the time the first Southern and Eastern Europeans arrived in the 1870s, they were referred to as “Hunkies,” a corruption of “Hungarians,” regardless of their country of origin. They were encouraged to live in certain neighborhoods, particularly Cambria City and Minersville (for more about the history of Cambria City, including current photos of historic buildings and churches, see the Walking Tour of Cambria City). In 1870, 20% of Johnstown’s population was foreign born, but in these neighborhoods 40% were immigrants. This trend was to become even more extreme – in 1880, 85% of Cambria City residents were foreign born, compared to 40% in Johnstown. Additional neighborhoods dominated by immigrants sprung up, including Prospect and Conemaugh. Living conditions were unsanitary, and infant mortality was high. From 1890 to 1910, the city’s population of Southern and Eastern European immigrants swelled from 2,400 to more than 12,000.

These new arrivals to Johnstown faced prejudice and difficult living conditions. From the time the first Southern and Eastern Europeans arrived in the 1870s, they were referred to as “Hunkies,” a corruption of “Hungarians,” regardless of their country of origin. They were encouraged to live in certain neighborhoods, particularly Cambria City and Minersville (for more about the history of Cambria City, including current photos of historic buildings and churches, see the Walking Tour of Cambria City). In 1870, 20% of Johnstown’s population was foreign born, but in these neighborhoods 40% were immigrants. This trend was to become even more extreme – in 1880, 85% of Cambria City residents were foreign born, compared to 40% in Johnstown. Additional neighborhoods dominated by immigrants sprung up, including Prospect and Conemaugh. Living conditions were unsanitary, and infant mortality was high. From 1890 to 1910, the city’s population of Southern and Eastern European immigrants swelled from 2,400 to more than 12,000.

Better jobs, with higher wages, safer working conditions and the opportunity to advance, were offered to native-born Americans first, and then immigrants from Wales, Scandinavia, Ireland and Germany. Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were forced to take jobs with lower wages and worse working conditions. Most had been peasant farmers in the Old Country, accustomed to working outside. The work in the mills and mines was dangerous, especially for these untrained workers, and many industrial accidents occurred. The management grouped immigrants by nationality into work crews so that they could communicate in their native languages – and also to prevent them from organizing. In fact, unionization did not come to Johnstown’s Bethlehem Steel plant until 1942.

Better jobs, with higher wages, safer working conditions and the opportunity to advance, were offered to native-born Americans first, and then immigrants from Wales, Scandinavia, Ireland and Germany. Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were forced to take jobs with lower wages and worse working conditions. Most had been peasant farmers in the Old Country, accustomed to working outside. The work in the mills and mines was dangerous, especially for these untrained workers, and many industrial accidents occurred. The management grouped immigrants by nationality into work crews so that they could communicate in their native languages – and also to prevent them from organizing. In fact, unionization did not come to Johnstown’s Bethlehem Steel plant until 1942.

In most cases, every member of an immigrant family had to work. Women ran boarding houses and gardened for fresh vegetables, helped by their daughters, while boys often left school early to work in the mills and mines alongside their fathers. Jewish families worked together at the stores they established. Economic survival in Johnstown remained a family effort until at least World War II – family goals were pursued as opposed to individual goals.

In most cases, every member of an immigrant family had to work. Women ran boarding houses and gardened for fresh vegetables, helped by their daughters, while boys often left school early to work in the mills and mines alongside their fathers. Jewish families worked together at the stores they established. Economic survival in Johnstown remained a family effort until at least World War II – family goals were pursued as opposed to individual goals.

Excluded from mainstream Johnstown culture, immigrants founded their own social and fraternal institutions. Initially, Eastern and Southern European immigrants created institutions that served newcomers regardless of national origin – but as their numbers increased, these institutions separated by ethnicity. Instead of village-based identities of the Old Country, immigrants to Johnstown identified with their ethnic or nationality group.

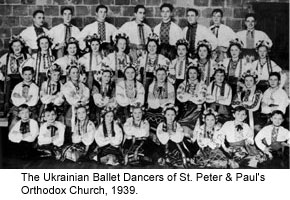

After World War I, the institutional network of ethnic parishes, clubs, societies and other institutions steadily expanded and diversified into a rich community. Immigrant groups published newspapers in a variety of languages, and opened stores and other small businesses. More than 100 ethnic social clubs were operating in Johnstown at one time, and many had their own lodges. Singing societies, instrumental bands, women’s clubs and even athletic teams were founded. Some fraternal organizations started as insurance societies, offering insurance and death benefits to their members, and then became social clubs as well. A few even offered citizenship classes to immigrants seeking to become naturalized. As immigrants’ numbers increased, they established their own ethnic churches – by 1910, 14 had been built. Many are still active parishes today.

After World War I, the institutional network of ethnic parishes, clubs, societies and other institutions steadily expanded and diversified into a rich community. Immigrant groups published newspapers in a variety of languages, and opened stores and other small businesses. More than 100 ethnic social clubs were operating in Johnstown at one time, and many had their own lodges. Singing societies, instrumental bands, women’s clubs and even athletic teams were founded. Some fraternal organizations started as insurance societies, offering insurance and death benefits to their members, and then became social clubs as well. A few even offered citizenship classes to immigrants seeking to become naturalized. As immigrants’ numbers increased, they established their own ethnic churches – by 1910, 14 had been built. Many are still active parishes today.

A small settlement of African-Americans was present on Laurel Mountain near Johnstown at least since 1825. There is evidence of Underground Railroad activity nearby during the 1830s, and the first area African-American church began meeting in a log cabin as early as 1840. A group of African-Americans came to work in a Woodvale tannery around 1870. However, African-Americans made up less than one percent of the population until 1919. World War I brought immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe to a screeching halt, but the need for workers continued to increase — so Cambria Steel (and later, Bethlehem) even sent representatives to Southern states to recruit Black workers. In 1910, Johnstown’s Black population was just 45, but by 1923 it had swelled to nearly 3,000. Groups of Mexicans also came to Johnstown to work during this period.

A small settlement of African-Americans was present on Laurel Mountain near Johnstown at least since 1825. There is evidence of Underground Railroad activity nearby during the 1830s, and the first area African-American church began meeting in a log cabin as early as 1840. A group of African-Americans came to work in a Woodvale tannery around 1870. However, African-Americans made up less than one percent of the population until 1919. World War I brought immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe to a screeching halt, but the need for workers continued to increase — so Cambria Steel (and later, Bethlehem) even sent representatives to Southern states to recruit Black workers. In 1910, Johnstown’s Black population was just 45, but by 1923 it had swelled to nearly 3,000. Groups of Mexicans also came to Johnstown to work during this period.

At the mill, Black workers were offered the least desirable jobs at the lowest pay, and white workers often limited their opportunities for advancement. Black workers and their families faced discrimination in the Johnstown community as well, including the infamous Rosedale incident of 1923, in which the mayor of Johnstown ordered all African Americans who had lived in town for less than seven years to leave.

The ethnic composition of Johnstown did not change significantly during the 1920s and 1930s. Serving together in the military during World War II helped break down the barriers faced by Southern and Eastern European immigrants and their children. In the post-war era, Southern and Eastern European groups became somewhat more assimilated into the rest of Johnstown society. Intermarriage with members of other ethnic groups became more common, and Southern and Eastern European immigrants were accepted into country clubs and other exclusive groups. Families began to move out of their traditional neighborhoods. Some young adults began to seek college degrees, particularly war veterans taking advantage of GI Bill benefits, which entitled them to one year of full-time college training plus a period equal to their time in service, up to a maximum of 48 months. It was no longer certain that boys would follow in their fathers’ footsteps and work in the steel mills and coal mines, although many continued to do so as long as the opportunity existed.

The ethnic composition of Johnstown did not change significantly during the 1920s and 1930s. Serving together in the military during World War II helped break down the barriers faced by Southern and Eastern European immigrants and their children. In the post-war era, Southern and Eastern European groups became somewhat more assimilated into the rest of Johnstown society. Intermarriage with members of other ethnic groups became more common, and Southern and Eastern European immigrants were accepted into country clubs and other exclusive groups. Families began to move out of their traditional neighborhoods. Some young adults began to seek college degrees, particularly war veterans taking advantage of GI Bill benefits, which entitled them to one year of full-time college training plus a period equal to their time in service, up to a maximum of 48 months. It was no longer certain that boys would follow in their fathers’ footsteps and work in the steel mills and coal mines, although many continued to do so as long as the opportunity existed.

The Heritage Discovery Center’s permanent exhibit, “America: Through Immigrant Eyes,” focuses on the period of immigration from about 1880 to 1914, which was dominated by Southern and Eastern Europeans. The exhibit tells their story, including why they left, what they found when they got here, and how they developed a rich cultural life that is still celebrated today.

Sources include: Ewa Morawska, “Johnstown’s Ethnic Groups,” in Johnstown: Story of a Unique Valley, 1984.