The 1889 flood killed one in ten people in Johnstown – but what about those who survived? Some survivors managed to make it to high ground in time, or to the upper floor of a building that withstood the flood. Others were washed away but somehow managed to survive the floodwaters, floating debris, and the horrific fire that broke out at the stone bridge. Everyone who survived had a story — and many of these stories were recorded, in memoirs, letters and media reports. Below is a sampling of a few of the most famous.

Anna Fenn Maxwell

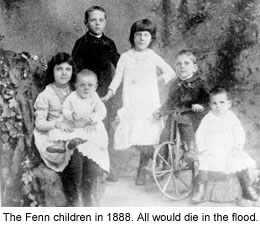

Anna Fenn MaxwellBefore the flood struck, Anna Fenn’s husband, John, was at a neighbor’s house, helping them move their furniture to higher ground. He was washed away moments before the flood struck the Fenn home, where Anna and the seven children were. Mrs. Fenn held the baby while the other six children clung to her, but one after the other they drowned. She described the scene as follows: “The water rose and floated us until our heads nearly touched the ceiling. . .It was dark and the house was tossing every way. The air was stifling, and I could not tell just the moment the rest of the children had to give up and drown. . .what I suffered, with the bodies of my seven children floating around me in the gloom can never be told.”

John Fenn also died in the flood. Mrs. Fenn gave birth to a baby girl a few weeks later, but the child did not survive. Eventually she remarried and moved to Richmond, Virginia, and apparently had no more children. She died in 1928, and her grave is marked with a large monument in Johnstown’s Grandview Cemetery.

John Fenn also died in the flood. Mrs. Fenn gave birth to a baby girl a few weeks later, but the child did not survive. Eventually she remarried and moved to Richmond, Virginia, and apparently had no more children. She died in 1928, and her grave is marked with a large monument in Johnstown’s Grandview Cemetery.

Victor Heiser, 16, was in his family’s barn on the fateful day of May 31. He glanced toward the house and saw his father at a second-story window, frantically gesturing for him to climb to the roof. He scrambled up, and saw what his father had seen – a two-story, rumbling mass of debris, crashing down the valley toward them. As he watched in horror, the Heiser home was crushed like an eggshell, and his parents disappeared. The barn was engulfed as well, and Heiser rode the violent flood wave downstream, avoiding freight cars, animals and other debris, until he passed a two-story brick house.

Victor Heiser, 16, was in his family’s barn on the fateful day of May 31. He glanced toward the house and saw his father at a second-story window, frantically gesturing for him to climb to the roof. He scrambled up, and saw what his father had seen – a two-story, rumbling mass of debris, crashing down the valley toward them. As he watched in horror, the Heiser home was crushed like an eggshell, and his parents disappeared. The barn was engulfed as well, and Heiser rode the violent flood wave downstream, avoiding freight cars, animals and other debris, until he passed a two-story brick house.

Desperately, he leapt for the roof of the house – he made it, and spent the night in the attic with 19 other survivors, praying the building wouldn’t collapse. His parents died in the flood, and the family’s downtown store was gone. All he had from his former life was a trunk from his parents’ house, filled with his father’s Civil War uniform, a few pieces of silver and his mother’s Bible – it had somehow survived the flood and been returned to Victor, the family’s sole survivor. He left Johnstown, went to college and eventually became a physician. As a public health officer and physician, Dr. Victor Heiser is credited with saving as many as two million lives, and developed the first effective treatment against leprosy. He wrote a best-selling memoir, and before his death in 1972 was interviewed by historian David McCullough. A recording of that interview is stored in the Johnstown Area Heritage Association’s archives.

George and Belle Waters had managed to move most of their family’s best things to the second floor of the house by the time the flood wave hit. Their three young daughters were at home, and their 7-year-old son was visiting a neighbor. Waters heard someone down the street shout a warning, and hurried his wife and daughters up a ladder into the unfinished attic, which had no floor. The family was forced to stand on joists – the lath and plaster ceiling between each joist could not support their weight. The water rose upstairs, and the family struggled to keep their balance as the house shook. Belle, holding baby Eva, fell through the ceiling but was able to keep her head above water by standing on tiptoe, balancing on a raised corner of the room. She lifted Eva above her shoulders. Mary and Margaret soon fell into the murky water too, and struggled amid the swirling debris. Desperate, George reached into the water and grabbed two feet and thought he only had one of the girls, and called in despair to his wife. But as he pulled the feet out of the murky water, he saw that he had both girls – one foot belonged to each. After Mary and Margaret were safe, he then found the ladder, went down into the submerged room and rescued Belle and Eva. After the flood subsided, the Waters family was overjoyed to discover that their son, Merle, had also survived. The family later rebuilt their house on the same site.

As a memento of the terrible flood, Belle saved the dress 5-year-old Mary had worn that fateful day. Although washed and ironed, it had been permanently stained slightly darker by the flood’s waters. The dress was donated to the Johnstown Flood Museum in 1989 by Mary Waters’ descendants and is on display in the relic case on the museum’s first floor.

Pastor of the Franklin Street Methodist Church, Chapman and his family lived in a parsonage in the middle of town. On the day of the flood, he opened his front door to see a boxcar rolling down the street with a man on top of it. The man grabbed for a tree limb and managed to make his way to the second floor of the Chapman home. The reverend quickly realized that the dam must have failed, and turned and yelled for his family to head for the attic. As the family scrambled for the stairs, Chapman rushed to the study to turn off the gas fire. The front door burst open and floodwater rushed in, chasing Chapman as he ran for the kitchen stairs. The family made it to safety in the attic, along with the man from the boxcar and a few others who had rescued themselves in a similar fashion.

Pastor of the Franklin Street Methodist Church, Chapman and his family lived in a parsonage in the middle of town. On the day of the flood, he opened his front door to see a boxcar rolling down the street with a man on top of it. The man grabbed for a tree limb and managed to make his way to the second floor of the Chapman home. The reverend quickly realized that the dam must have failed, and turned and yelled for his family to head for the attic. As the family scrambled for the stairs, Chapman rushed to the study to turn off the gas fire. The front door burst open and floodwater rushed in, chasing Chapman as he ran for the kitchen stairs. The family made it to safety in the attic, along with the man from the boxcar and a few others who had rescued themselves in a similar fashion.

But the rush of the floodwater was overpowering, and the survivors didn’t know if the house would hold. The force of the water tore the porches off the house and toppled bookcases and other furniture downstairs, making noises that terrified the group. “I think none of us was afraid to meet God, but we all felt willing to put it off until a more propitious time,” Chapman later wrote. Finally the noise subsided, and Chapman and the others looked out on “a scene of utter desolation.” Chapman’s church, the Franklin Street Methodist Church, had also survived. In fact, the church had borne the brunt of the flood wave, helping protect several buildings behind it – including the parsonage and Alma Hall.

Alma Hall was located on Main Street, and was Johnstown’s tallest structure. Before the terrible night of May 31 was over, Alma Hall would shelter 264 desperate flood survivors on its upper floors. The survivors huddled together in the dark without dry clothes, food or medical supplies, wondering if the building would collapse. Among them was the Rev. Dr. David Beale of the Presbyterian Church on Main Street, who had been in his parsonage at the time the flood wave hit. He and his family had managed to make it to the third floor of the house. They were able to save several people floating by, but as the night went on the house seemed less stable. The group left the house, walking on flood wreckage, and made it to Alma Hall, which was about a block away. Beale later led the assembly in prayer.

Alma Hall was located on Main Street, and was Johnstown’s tallest structure. Before the terrible night of May 31 was over, Alma Hall would shelter 264 desperate flood survivors on its upper floors. The survivors huddled together in the dark without dry clothes, food or medical supplies, wondering if the building would collapse. Among them was the Rev. Dr. David Beale of the Presbyterian Church on Main Street, who had been in his parsonage at the time the flood wave hit. He and his family had managed to make it to the third floor of the house. They were able to save several people floating by, but as the night went on the house seemed less stable. The group left the house, walking on flood wreckage, and made it to Alma Hall, which was about a block away. Beale later led the assembly in prayer.

Other notable Alma Hall stories include that of James Walters, a lawyer, who was washed out of his home on Walnut Street, onto a floating roof, and was thrown by the force of the water through a window into his own office in Alma Hall. Despite having suffered two broken ribs himself, Dr. William Matthews tended to the wounded by the dim light of distant fires, and delivered two babies. It was, according to Beale, “a night of indescribable horrors.” Alma Hall is still a Johnstown landmark today.

For more, visit the section about the 1889 flood in the Archives & Research section of this site.

More 1889 flood resources