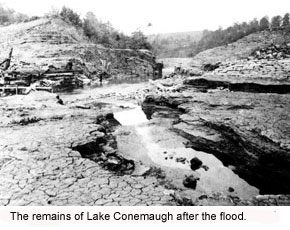

The Western Reservoir (later renamed Lake Conemaugh) had been constructed not for recreation, but instead to provide water for the section of the Pennsylvania Canal between Johnstown and Pittsburgh. However, the canal system became obsolete almost immediately after the reservoir was completed in 1852. Very little maintenance was performed on the dam during its existence, even though it broke once already in 1862 (this break caused very little damage, as the reservoir was only half full). In fact, one owner removed the drainage pipes beneath the dam to sell them for scrap, which meant there was no way to drain the reservoir for repairs. The reservoir and dam passed through several hands before the South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club bought it in 1879.

The South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club counted many of Pittsburgh’s leading industrialists and financiers among its 61 members, including Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Mellon, and Philander Knox. (Click here for a complete list of club members). Organized in 1879, the purpose of the club was to provide the members and their families an opportunity to get away from the noise, heat and dirt of Pittsburgh. The club owned the Western Reservoir, the dam that created it, and about 160 acres of land in the area. The club renamed the reservoir, calling it Lake Conemaugh. A 47-room clubhouse, featuring a huge dining room that could seat 150, was the main building on the club’s land. There were also 16 privately-owned “cottages,” actually houses of a generous size, along the lake’s shores. The club’s boat fleet included a pair of steam yachts, many sailboats and canoes, and boathouses to store them in.

The South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club counted many of Pittsburgh’s leading industrialists and financiers among its 61 members, including Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Mellon, and Philander Knox. (Click here for a complete list of club members). Organized in 1879, the purpose of the club was to provide the members and their families an opportunity to get away from the noise, heat and dirt of Pittsburgh. The club owned the Western Reservoir, the dam that created it, and about 160 acres of land in the area. The club renamed the reservoir, calling it Lake Conemaugh. A 47-room clubhouse, featuring a huge dining room that could seat 150, was the main building on the club’s land. There were also 16 privately-owned “cottages,” actually houses of a generous size, along the lake’s shores. The club’s boat fleet included a pair of steam yachts, many sailboats and canoes, and boathouses to store them in.

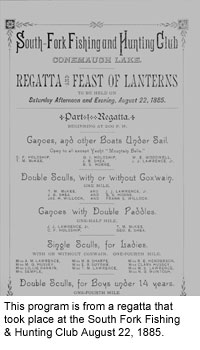

Entertainments included an annual regatta, theatricals and musical performances. Fishing and boating were popular activities, and the club members also enjoyed picnicking by the reservoir’s spillway. The club’s activities were beautifully documented by member Louis Semple Clarke, a talented amateur photographer (as seen in the shot below — more of Clarke’s work can be seen on the Historic Pittsburgh website, thanks to a collaboration between JAHA and Pitt-Johnstown).

The club did engage in periodic maintenance of the dam, but made some harmful modifications to it. They installed fish screens across the spillway to keep the expensive game fish from escaping, which had the unfortunate effect of capturing debris and keeping the spillway from draining the lake’s overflow. They also lowered the dam by a few feet in order to make it possible for two carriages to pass at the same time, so the dam was only about four feet higher than the spillway. The club never reinstalled the drainage pipes so that the reservoir could be drained.

The club did engage in periodic maintenance of the dam, but made some harmful modifications to it. They installed fish screens across the spillway to keep the expensive game fish from escaping, which had the unfortunate effect of capturing debris and keeping the spillway from draining the lake’s overflow. They also lowered the dam by a few feet in order to make it possible for two carriages to pass at the same time, so the dam was only about four feet higher than the spillway. The club never reinstalled the drainage pipes so that the reservoir could be drained.

When the dam broke on May 31, 1889, only about a half-dozen members were on the premises, as it was early in the summer season. They left immediately following the disaster, and the club members were largely silent about the tragedy. A small crowd of angry flood survivors went up to the club and broke into some of the buildings, breaking windows and destroying furniture, but no major damage was done.

When the dam broke on May 31, 1889, only about a half-dozen members were on the premises, as it was early in the summer season. They left immediately following the disaster, and the club members were largely silent about the tragedy. A small crowd of angry flood survivors went up to the club and broke into some of the buildings, breaking windows and destroying furniture, but no major damage was done.

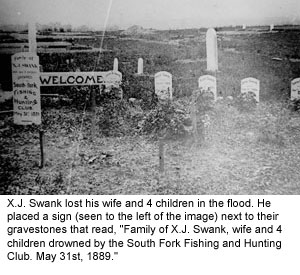

No other disaster prior to 1900 was so fully described. Writing for the masses, journalists exaggerated, repeated unfounded myths, and denounced the South Fork Club. As coverage of the horror of the event began to recede, the media began to look at the causes of the disaster. Residents of Johnstown, and Americans in general, began to turn their wrath toward the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. Newspapers all across the country denounced the sportsmen’s lake. The Chicago Herald’s editorial on the responsibility of the South Fork Club was entitled “Manslaughter or Murder?” On June 9, the Herald carried a cartoon that showed the members of the club drinking champagne on the porch of the clubhouse while, in the valley beneath them, the Flood is destroying Johnstown. In Johnstown, the Tribune resumed publication on June 14. In the first edition following the disaster, the Tribune’s editor George Swank placed blame for the disaster clearly on the Club: “We think we know what struck us, and it was not the work of Providence. Our misery is the work of man.” A New York Times headline read, ” An Engineering Crime – The Dam of Inferior Construction, According to the Experts,” A New York World headline on June 7 declared “The Club Is Guilty.” However, most news articles did not mention club members by name.

No other disaster prior to 1900 was so fully described. Writing for the masses, journalists exaggerated, repeated unfounded myths, and denounced the South Fork Club. As coverage of the horror of the event began to recede, the media began to look at the causes of the disaster. Residents of Johnstown, and Americans in general, began to turn their wrath toward the members of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club. Newspapers all across the country denounced the sportsmen’s lake. The Chicago Herald’s editorial on the responsibility of the South Fork Club was entitled “Manslaughter or Murder?” On June 9, the Herald carried a cartoon that showed the members of the club drinking champagne on the porch of the clubhouse while, in the valley beneath them, the Flood is destroying Johnstown. In Johnstown, the Tribune resumed publication on June 14. In the first edition following the disaster, the Tribune’s editor George Swank placed blame for the disaster clearly on the Club: “We think we know what struck us, and it was not the work of Providence. Our misery is the work of man.” A New York Times headline read, ” An Engineering Crime – The Dam of Inferior Construction, According to the Experts,” A New York World headline on June 7 declared “The Club Is Guilty.” However, most news articles did not mention club members by name.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, the club contributed 1,000 blankets to the relief effort. A few of the club members, most notably Robert Pitcairn, served on relief committees. About half of the club members also contributed to the disaster relief effort, including Andrew Carnegie, whose company contributed $10,000. Later, he would rebuild Johnstown’s library – that library building today houses the Johnstown Flood Museum. However, no club member ever expressed a sense of personal responsibility for the disaster.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, the club contributed 1,000 blankets to the relief effort. A few of the club members, most notably Robert Pitcairn, served on relief committees. About half of the club members also contributed to the disaster relief effort, including Andrew Carnegie, whose company contributed $10,000. Later, he would rebuild Johnstown’s library – that library building today houses the Johnstown Flood Museum. However, no club member ever expressed a sense of personal responsibility for the disaster.

The club had very few assets aside from the clubhouse, but a few lawsuits were brought against the club anyway. Legal action against individual club members was difficult if not impossible, as it would have been necessary to prove personal negligence – and the power and influence of the club members is hard to overestimate. In the end, no lawsuit against the club was successful.

The Johnstown Flood resulted in the first expression of outrage at power of the great trusts and giant corporations that had formed in the post-Civil War period. This antagonism was to break out into violence during the 1892 Homestead steel strike in Pittsburgh. The Club’s great wealth rather than the dam’s engineering came to be condemned. The Johnstown Flood became emblematic of what many Americans thought was going wrong with America. In simple terms, many saw the Club members as “robber barons” who had gotten away with murder.

For more, visit the section about the 1889 flood in the Archives & Research section of this site.

More 1889 flood resources