The great Johnstown flood of 1889 is remembered as the worst disaster by dam failure in American history. In fact, it was the greatest single-day civilian loss of life in this country before September 11, 2001. The 1889 flood was the biggest news story of its era, and the biggest scandal, as many of the leading industrialists of the day were members of the club that owned the dam. The relief effort was the first major peacetime disaster for Clara Barton and the fledgling American Red Cross. These are just some of the reasons the 1889 Johnstown flood is so important in American history, and why the Johnstown Flood Museum is almost exclusively devoted to telling its story.

The great Johnstown flood of 1889 is remembered as the worst disaster by dam failure in American history. In fact, it was the greatest single-day civilian loss of life in this country before September 11, 2001. The 1889 flood was the biggest news story of its era, and the biggest scandal, as many of the leading industrialists of the day were members of the club that owned the dam. The relief effort was the first major peacetime disaster for Clara Barton and the fledgling American Red Cross. These are just some of the reasons the 1889 Johnstown flood is so important in American history, and why the Johnstown Flood Museum is almost exclusively devoted to telling its story.

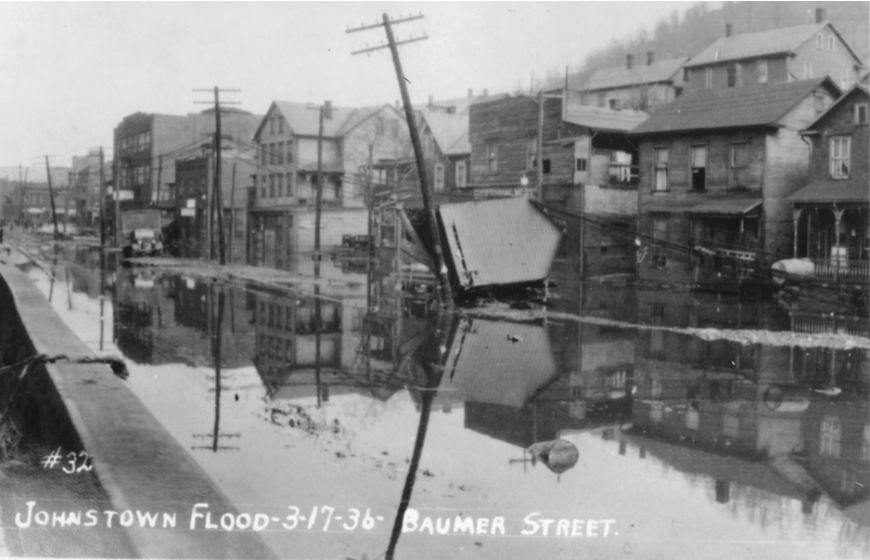

However, the 1889 flood is not the only flood in Johnstown’s history that caused significant loss of life and property damage. The most famous of these occurred in 1936 and 1977. An exhibition of photographs of the 1977 flood by Merle Agnello of the Tribune-Democrat is shown in the stairwell of the Johnstown Flood Museum, and some photographs of the 1936 flood are also on display. Markers showing the high-water level for the 1889, 1936 and 1977 floods can be seen on the exterior corner of Johnstown’s City Hall.

On March 17, 1936, Johnstown experienced a devastating flood caused by heavy runoff from melting snow and three days of rain. Before the waters receded the following day, the flood had risen to 14 feet in some areas. About two dozen people died in the flood, while 77 buildings were destroyed– nearly 3,000 more were severely damaged. Property damages were estimated at $41 million.

The disaster became the catalyst for major federal support to rehabilitate Johnstown. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) mustered every available man in a four-county area to provide assistance-some 7,000 men and 350 trucks were set to the task of digging out the town. After the flood wreckage had been cleared, long-term public works programs began, such as replacing sidewalks, roads and bridges.

But Johnstowners wanted more, and the White House was swamped with 15,000 letters from local people pleading for help. President Franklin D. Roosevelt responded by touring Johnstown, and authorizing the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to channelize the rivers through town, at a cost of $8.7 million. The goal of the Local Flood Protection Program was to increase the capacity of the rivers to prevent future flooding.

An interesting sidenote to the story of the 1936 flood is the so-called “Johnstown flood tax.” In the immediate aftermath of the 1936 flood, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed a 10% tax on alcohol to assist in flood recovery efforts. (A relevant bit of context is that this was in the immediate post-Prohibition era, when many states were beginning to place taxes on alcohol.) The revenues collected were initially used to benefit flood victims and rebuild the town, but since the 1940s the money has gone into general funds. The tax was extended several times before being made permanent in 1951 (and was even increased twice in the 1960s). Various proposals to change the law have included going to a per-drink tax, using the funds to “relieve economic catastrophes,” or helping with city financing. But although the tax seems to come up frequently, to date no proposed changes to the “1936 Johnstown flood tax” have become law, so the somewhat misleading name persists.

Some fascinating first-person accounts of the 1936 flood have been digitized and placed on our website under the Archives & Research section of this site.

A line of severe thunderstorms stalled over Johnstown on July 20, 1977, dropping as much as a foot of rain in some areas. Small streams – Solomon’s Run, Sam’s Run, Peggy’s Run – carved new channels and smashed through expressways, apartment buildings, factories and homes. An earthen water supply dam collapsed at Laurel Run Reservoir, one of several dams that failed. The waters overflowed the channel system in Johnstown that was to have left the city “flood-free.” However, according to later estimates by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the water level could have been as much as 11 feet higher if the channel system had never been built.

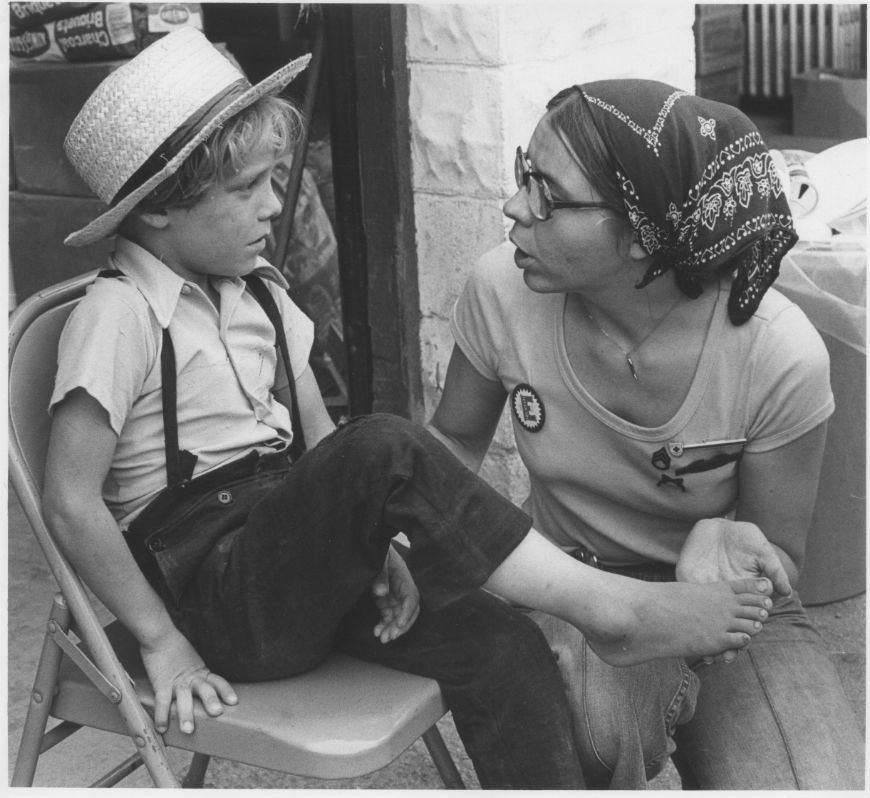

The Red Cross, Salvation Army, other non-profit agencies, the state and federal governments, and private individuals rushed to help. On July 21, President Jimmy Carter declared the worst-hit counties a federal disaster area (Cambria, Somerset, Indiana, Bedford, Westmoreland, Clearfield, and Jefferson; a few days later, Blair was added). The National Guard was mobilized, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers arrived to assist in debris removal and demolition of non-salvageable buildings.

The death toll would reach 85, while property damages reached the $300 million mark. Hundreds of people were left homeless, and took shelter in churches, schools, fire halls and even dormitories at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. After the immediate crisis was over, many small trailer home parks were established to accommodate those left homeless.

Over the next year, the federal government spent some $200 million in the area, rebuilding damaged public facilities and lending funds or giving grants to property owners for repairs and construction.

The 1977 flood was a blow to Johnstown’s increasingly fragile economy. Many downtown firms damaged by the flood did not reopen or moved to the suburbs. Employment at Bethlehem Steel dropped by 4,000. Between 1970 and 1980, the city’s population dropped from 42,221 to 34,221, a 19.4% decline, and the 1977 flood is a major reason why.

You can listen to oral histories of the 1977 flood in the Archives & Research section of this site.