The historical importance of the Johnstown flood is magnified by the response of the nation and the world. In the immediate aftermath of the flood, the avalanche of graphic newspaper reports fueled an enormous charitable outpouring. Goods, services and money were donated, and volunteers came to town to help in the huge task of rebuilding the city. The nation’s public was fascinated by the disaster, and books, photographs and other flood memorabilia were in great demand.

The historical importance of the Johnstown flood is magnified by the response of the nation and the world. In the immediate aftermath of the flood, the avalanche of graphic newspaper reports fueled an enormous charitable outpouring. Goods, services and money were donated, and volunteers came to town to help in the huge task of rebuilding the city. The nation’s public was fascinated by the disaster, and books, photographs and other flood memorabilia were in great demand.

Immediately following the disaster, the first message to the outside world was sent by telegraph from Sang Hollow tower, located below Johnstown. Robert Pitcairn, superintendent of the railroad and a member of the South Fork Fishing & Hunting Club, was on a train held at Sang Hollow when flood debris and survivors began floating downstream. Pitcairn alerted Pittsburgh that Johnstown had been destroyed and that help should be organized immediately. The first relief train from Pittsburgh reached Johnstown on Sunday morning, June 2.

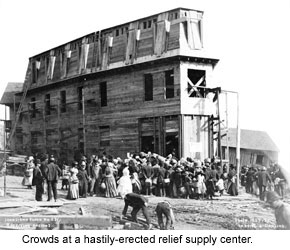

The immediate relief of Johnstown was a huge undertaking. Some 25,000 survivors needed to be fed, clothed, housed, and cared for. Four square miles of downtown Johnstown had been completely destroyed, and 1,600 residences were ruined. The American Red Cross was one of several relief agencies who came to assist. Among the first workers who came from Pittsburgh were 55 undertakers, and 9 temporary morgues were established. Recovery of the dead continued for months; it was not until July 10 that a day passed without the recovery of a single corpse. Bodies were found as far away as Cincinnati (600 miles), and as late as 1911. The morgues kept very careful records, but nearly one in three of the victims were never identified.

The immediate relief of Johnstown was a huge undertaking. Some 25,000 survivors needed to be fed, clothed, housed, and cared for. Four square miles of downtown Johnstown had been completely destroyed, and 1,600 residences were ruined. The American Red Cross was one of several relief agencies who came to assist. Among the first workers who came from Pittsburgh were 55 undertakers, and 9 temporary morgues were established. Recovery of the dead continued for months; it was not until July 10 that a day passed without the recovery of a single corpse. Bodies were found as far away as Cincinnati (600 miles), and as late as 1911. The morgues kept very careful records, but nearly one in three of the victims were never identified.

The Johnstown Flood developed into the biggest news story of the era. Relief committees were organized in all the larger American cities. In Paris, Buffalo Bill Cody gave a benefit for the flood fund on June 13. Charity also included food and goods of every kind: Cincinnati sent 20,000 pounds of ham and prisoners of Western Penitentiary in Pittsburgh baked 1000 loaves of bread a day. The Standard Oil Company shipped a carload of kerosene to Johnstown. This vast stream of goods continued for months. When an accounting was attempted, it was estimated that 1,408 full carloads of goods, weighing 17,000,000 pounds, had been sent to Johnstown.

The Johnstown Flood developed into the biggest news story of the era. Relief committees were organized in all the larger American cities. In Paris, Buffalo Bill Cody gave a benefit for the flood fund on June 13. Charity also included food and goods of every kind: Cincinnati sent 20,000 pounds of ham and prisoners of Western Penitentiary in Pittsburgh baked 1000 loaves of bread a day. The Standard Oil Company shipped a carload of kerosene to Johnstown. This vast stream of goods continued for months. When an accounting was attempted, it was estimated that 1,408 full carloads of goods, weighing 17,000,000 pounds, had been sent to Johnstown.

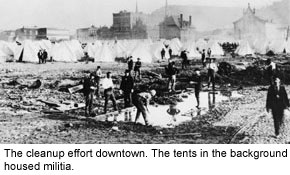

The flood recovery effort was initially led by Johnstown residents, and then by the Pittsburgh Relief Committee. Governor James A. Beaver created the Pennsylvania Relief Committee to take over the task, and called out the Pennsylvania militia to maintain order in the town. With up to 10,000 men working in the valley, the cleanup and recovery work moved along with surprising speed. In just 14 days, the Pennsylvania Railroad had rebuilt 20 miles of track and bridges, allowing it to reopen its line to the east.

The flood recovery effort was initially led by Johnstown residents, and then by the Pittsburgh Relief Committee. Governor James A. Beaver created the Pennsylvania Relief Committee to take over the task, and called out the Pennsylvania militia to maintain order in the town. With up to 10,000 men working in the valley, the cleanup and recovery work moved along with surprising speed. In just 14 days, the Pennsylvania Railroad had rebuilt 20 miles of track and bridges, allowing it to reopen its line to the east.

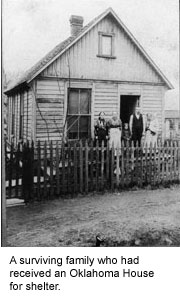

Initially, homeless residents crowded into houses on hillsides or built dwellings from wreckage. Later in the summer, prefabricated “Oklahoma” houses (named for the 1889 Oklahoma land rush) began to appear in Johnstown. Six weeks after the Flood, the town was well on its way to recovery – the river channels had been cleared and huge piles of wreckage had been removed. By July, you could buy ice cream for the July 4 celebration. The truly critical element in the recovery of Johnstown was the resumption of activity at the Cambria Iron Works. On June 9, company officials announced that the mill would be rebuilt.

Initially, homeless residents crowded into houses on hillsides or built dwellings from wreckage. Later in the summer, prefabricated “Oklahoma” houses (named for the 1889 Oklahoma land rush) began to appear in Johnstown. Six weeks after the Flood, the town was well on its way to recovery – the river channels had been cleared and huge piles of wreckage had been removed. By July, you could buy ice cream for the July 4 celebration. The truly critical element in the recovery of Johnstown was the resumption of activity at the Cambria Iron Works. On June 9, company officials announced that the mill would be rebuilt.

Millions of words of news coverage poured out of Johnstown for weeks and months after the disaster. Nearly all Eastern and Midwestern dailies sent correspondents to Johnstown, and about 100 reporters came to cover the story. The Flood correspondents worked under primitive conditions — some lived in a brick works and called themselves the Lime Kiln Club. The Flood was the foundation for several major journalistic careers, including that of Richard Harding Davis.

Millions of words of news coverage poured out of Johnstown for weeks and months after the disaster. Nearly all Eastern and Midwestern dailies sent correspondents to Johnstown, and about 100 reporters came to cover the story. The Flood correspondents worked under primitive conditions — some lived in a brick works and called themselves the Lime Kiln Club. The Flood was the foundation for several major journalistic careers, including that of Richard Harding Davis.

The record news coverage brought on a rush of popular charity; $3,742,818.78 was collected for the relief effort from within the U.S. and 12 foreign countries. The reports from Johnstown literally wrung the hearts and purses of the American people.

For more, visit the section about the 1889 flood in the Archives & Research section of this site.

More 1889 flood resources